How does a flood-prone city run out of water? Inside Chennai’s ‘Day Zero’ crisis

India's sixth largest city, with over 10 million inhabitants, currently faces a severe drinking water crisis. Photo: Denis Vostrikov|123rf

Chennai, India faced a devastating flood in 2015 that killed hundreds of people and displaced many more. Today, the southern Indian city’s four main reservoirs are virtually dry, writes Raj Bhagat Palanichamy, Senior Project Associate at World Resources Institute (WRI) India Sustainable Cities.

This crisis is not only due to lack of water. Lack of proper management is exacerbating dry conditions in Chennai and many other cities around the world. If Chennai does not take action, it will likely face similar crises in the future.

Chennai’s water crisis is a management problem

Chennai gets its water from four main reservoirs—Puzhal, Cholavaram, Chembarambakkam and Poondi. Puzhal and Cholavaram have completely dried up. Chembarambakkam and Poondi have little water left. While recent rainfall has brought a temporary reprieve, reservoirs are unlikely to recharge until the North East Monsoon arrives later in the year.

Two of the reservoirs supplying the city have completely dried up. Image: Copernicus and Sentinel Hub|WRI

In the meantime, the city and many of its more than 10 million residents are now desperately drawing water from wells, further depleting scant groundwater resources. Others wait in line for hours to get water that is trucked in from other locations or pay exorbitant sums to private water providers.

While last year’s poor monsoon season contributed to the current crisis, Chennai’s water scarcity has worsened in recent decades, driven largely by unplanned urbanisation and increased consumption.

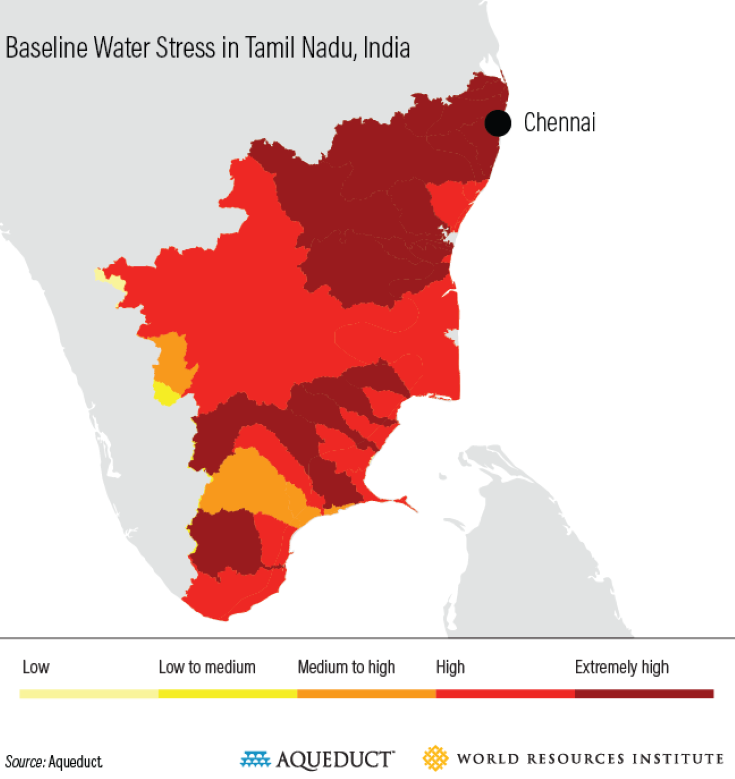

Chennai’s population has increased from 500,000 to more than 10 million over the last century. Its economy and appetite for water-intensive industry, products and agriculture have grown in-step with population. According to WRI’s Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas, Chennai faces extremely high baseline water stress, meaning that on average more than 80 per cent of the available water supply is used up every year by agriculture, industries and consumers.

India is one of 36 countries that are deemed to be water-stressed according to WRI. Image: Aqueduct|WRI

At the same time, the water that is available is becoming increasingly polluted. Dumping untreated sewage into lakes is common practice in Chennai. These pollutants also seep into the soil and affect groundwater, further worsening the city’s water security.

Five things Chennai can do to increase water security

Many have proposed ideas such as bringing water from other watersheds or investing in desalination plants to provide water to the increasingly water-stressed Chennai. However, bringing water from distant watersheds such as Cauvery or Krishna wouldn’t help the city in the long run, as these watersheds are also facing water-scarcity issues. Desalination plants could address some of the concerns, but they are very costly and consume a lot of energy. Chennai’s government is in the throes of a crisis – a difficult situation in which immediate action must be taken to sustain residents until the monsoons come. The city should also think about taking steps to help avert a similar situation in the future:

Harvest rainwater: a simple option for the city is to better enforce existing laws related to rainwater harvesting in buildings. Rapid urbanisation has brought more pavement into the city, which prevents groundwater recharge and rainwater absorption. Recharge points like green spaces and wetlands can absorb stagnant water from roads and increase groundwater levels. Corporations could also fund these solutions as part of their corporate social responsibility programs

Reuse wastewater: The Cooum and Adyar rivers carry a huge amount of sewage into the sea every day. Multiple lakes across the city have also been affected by sewage dumping. Small sewage treatment plants combined with apartment-level sewage treatment systems could help treat the sewage without using up more land. The treated sewage water could be reused for non-potable purposes (such as running HVAC systems, flushing toilets and landscaping) across the city while improving water quality overall

Conserve lakes and flood plains: Chennai’s master plan must incorporate the protection of lakes and associated flood plains. Flood plains are the biggest recharge points. They also help prevent floods. Rapid construction over flood plains has made Chennai vulnerable to both floods and drought. The Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority should immediately take steps to stop construction over floodplains and consider providing incentives to prioritise developments over ridges instead

Open data: Part of the problem is that the government does not provide open and transparent data on water resources and uses, such as the extent of water pipes and how much water flows through them every day. More research and analysis could be done with open data, which could help lead to better solutions. Many experts in the industry and academia would be able to pool their thoughts and ideas if data were made available to them

Improve efficiency: Agriculture is the biggest consumer of water resources around the world, and India is no exception. Improvements in irrigation efficiency can increase available water resources for other sectors, including municipal users. Although many of India’s farmers, most of whom are small scale, cannot implement high-cost irrigation systems, new financing models can help. City governments could explore and implement policies to invest in and improve rural irrigation systems. Without addressing rural and agricultural water, Chennai (or any part of Tamil Nadu, the state where Chennai is located) is unlikely to solve its water crisis

Ensuring water-secure futures for cities like Chennai

While Chennai’s ‘Day Zero’ water shut-off was the latest to make headlines, cities around the world face similar problems. Cape Town, South Africa experienced a similar situation a year ago. Sao Paulo, Brazil nearly ran out of water in 2014 and experienced another severe drought last year. WRI’s Aqueduct tool shows that 36 countries are considered ‘extremely water stressed’, where more than 80 per cent of the available supply is used up every year by agriculture, industry and consumers.

Cities around the world cannot afford to wait. They need to implement sustainable solutions with a focus on integrated water resource management to avoid having their own ‘Day Zero’ experience. Chennai and other cities like it could be water-secure again, but only if we start acting now.

Read the original blog on the WRI website here. This article is reproduced with permission under Creative Commons.

Image credit: pytyczech|123rf