Climate change could force more than one million to migrate within countries by 2050

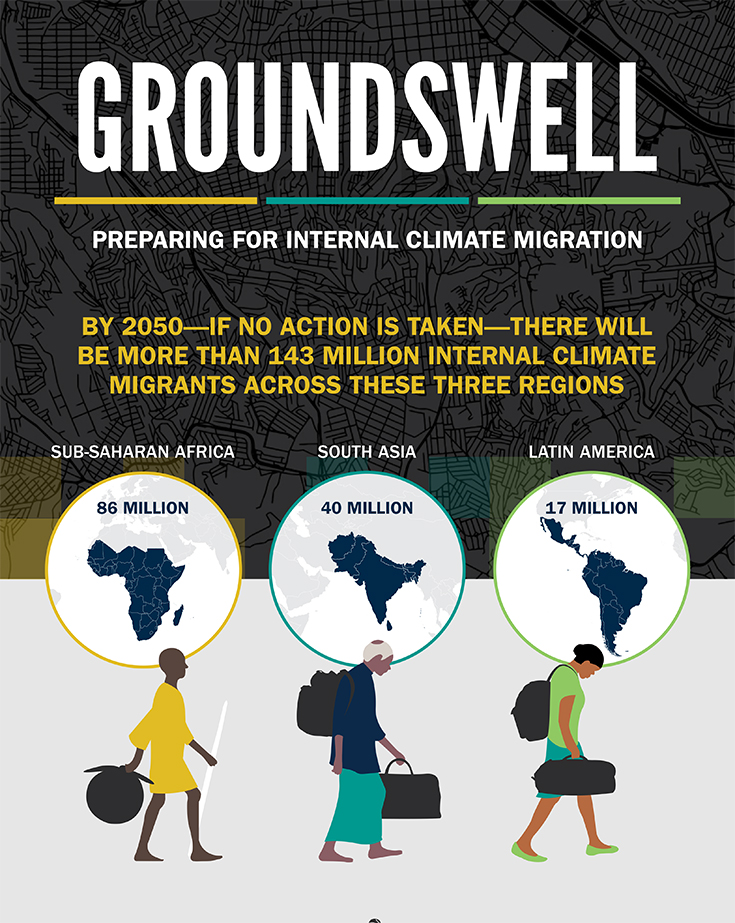

The worsening impacts of climate change in three densely populated regions of the world could see more than 140 million people move within their countries’ borders by 2050, creating a looming human crisis and threatening the development process, a new World Bank Group report finds.

Infographics: World Bank

But with concerted action – including global efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions and robust development planning at the country level – this worst-case scenario of over 140m could be dramatically reduced, by as much as 80 per cent, or more than 100 million people.

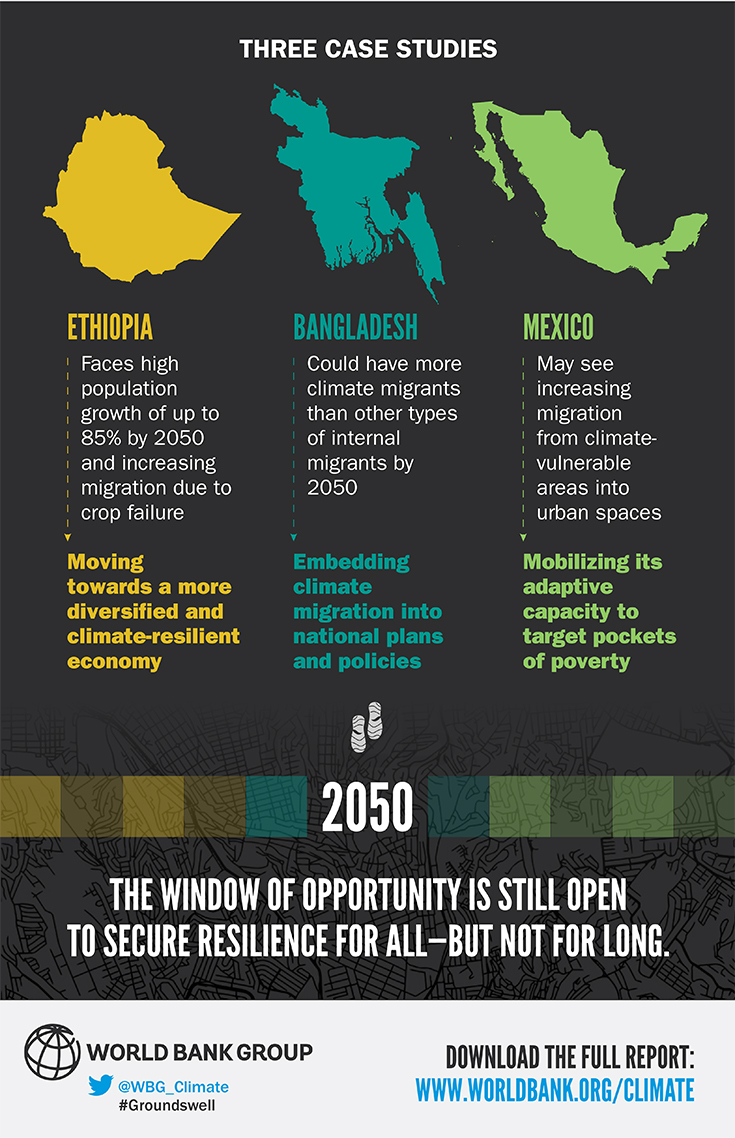

The report, Groundswell – Preparing for Internal Climate Migration (click here for World Bank YouTube video) is the first and most comprehensive study of its kind to focus on the nexus between slow-onset climate change impacts, internal migration patterns and, development in three developing regions of the world: Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America.

It finds that unless urgent climate and development action is taken globally and nationally, these three regions together could be dealing with tens of millions of internal climate migrants by 2050. These are people forced to move from increasingly non-viable areas of their countries due to growing problems like water scarcity, crop failure, sea-level rise and storm surges.

These ‘climate migrants’ would be additional to the millions of people already moving within their countries for economic, social, political or other reasons, the report warns.

World Bank Chief Executive Officer Kristalina Georgieva said the new research provides a wake-up call to countries and development institutions. “We have a small window now, before the effects of climate change deepen, to prepare the ground for this new reality,” Georgieva said. “Steps cities take to cope with the upward trend of arrivals from rural areas and to improve opportunities for education, training and jobs will pay long-term dividends. It’s also important to help people make good decisions about whether to stay where they are or move to new locations where they are less vulnerable.”

The research team, led by World Bank Lead Environmental Specialist Kanta Kumari Rigaud and including researchers and modellers from CIESIN Columbia University, CUNY Institute of Demographic Research, and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research - applied a multi-dimensional modelling approach to estimate the potential scale of internal climate migration across the three regions.

They looked at three potential climate change and development scenarios, comparing the most ‘pessimistic’ (high greenhouse gas emissions and unequal development paths), to ‘climate friendly’ and ‘more inclusive development’ scenarios in which climate and national development action increases in line with the challenge. Across each scenario, they applied demographic, socioeconomic and climate impact data at a 14-square kilometre grid-cell level to model likely shifts in population within countries.

This approach identified major hotspots of climate in- and out-migration - areas from which people are expected to move and urban, peri-urban and rural areas to which people will try to move to build new lives and livelihoods.

“Without the right planning and support, people migrating from rural areas into cities could be facing new and even more dangerous risks,” said the report’s team lead Kanta Kumari Rigaud. “We could see increased tensions and conflict as a result of pressure on scarce resources. But that doesn’t have to be the future. While internal climate migration is becoming a reality, it won’t be a crisis if we plan for it now.”

The report recommends key actions nationally and globally, including:

-

Cutting global greenhouse gas emissions to reduce climate pressure on people and livelihoods, and to reduce the overall scale of climate migration;

-

Transforming development planning to factor in the entire cycle of climate migration (before, during and after migration); and

-

Investing in data and analysis to improve understanding of internal climate migration trends and trajectories at the country level.

Thumbnail image: Jeffrey Thompson/123rf