Drinking water: Carbon pricing revenues could close infrastructure gaps

"It is possible to finance the drinking water supply in the majority of countries worldwide by the year 2030," says Dr Michael Jacob, lead author of a study from the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC) in Berlin, Germany.

In India alone, a carbon tax would generate around 115 billion US dollars a year: "And only a fraction of that would be needed for clean water, meaning that enough money would remain for sanitation and electricity," according to the researcher. In fact, the infrastructure needed for this second largest country of the world would consume only about four per cent of revenue from the tax.

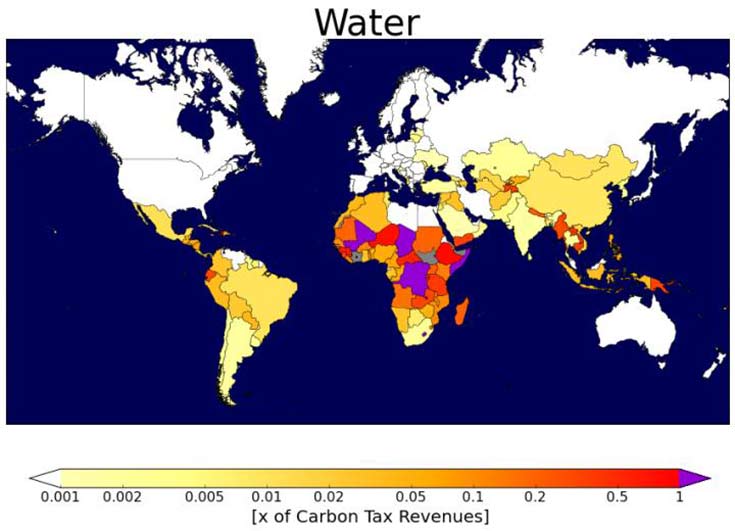

Share of carbon pricing revenues required to finance universal access to water infrastructure under domestic carbon pricing (ie, without transfers between countries) for an average 2°C scenario. The darker the colour, the higher the share, with dark purple shares exceeding 100%. White areas denote countries for which data are not available. Please note the logarithmic scale (Jakob, et al 2016)

That said, there are a few countries, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa (see figure above), where carbon pricing would not suffice, namely because carbon emissions there are so low that they would yield little revenue. "However, this funding gap could be closed when considering that developing countries have not yet exhausted their right to use the atmosphere," says Jakob. "Avoidance of emissions would then entitle them to compensation payments from industrialised countries."

The MCC study examined the development potential not only for water, sanitation and electricity, but also ICT and roads, was published yesterday under the title "Carbon pricing revenues could close infrastructure gaps" in the journal World Development.

In their calculations, the researchers assume that every country in the world is now introducing a steadily increasing carbon tax. In 2020 the tax would have to be 40 US dollars per tonne of CO2 emissions and increase up to 175 US dollars by 2030.

"In addition to generating revenue for infrastructure, the tax would thus contribute to the international goal of limiting global warming to two degrees," explains Dr Sabine Fuss, co-author of the study, who is also a guest researcher at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA). "This is because the tax penalises the use of fossil fuels and creates incentives for zero-carbon technologies."

Money not needed for the infrastructure could be used to mitigate climate change impacts such as rising sea levels, which affect developing countries in particular.

As is well known, raising the price of coal, oil and gas as part of climate protection measures brings its share of problems. "Nobody wants to pay more. But that's exactly why the idea to fund vital infrastructure directly from carbon revenue has clout," says Jakob. Linking the revenue to a specific use increases acceptance among the population and decreases the risk of misappropriation. In addition, carbon pricing could be used to reduce the burdens facing poorer segments of the population, such as the value added tax. "One thing is clear: For climate protection to be effective it must be embedded in a broader sustainable development scheme, and vice versa," according to Jakob. "Simply infusing more money won't solve the problem. Instead, decisive factors such as a functioning state, democratic decision-making and the relevant institutions must be taken into consideration."

Jakob, M, Chen, C, Fuss, S, Marxen, A, Rao, N, Edenhofer, O (2016): Carbon pricing revenues could close infrastructure gaps. World Development