Japan’s moonlanding puts focus back onto global peace

As the world continues towards an increasingly volatile space environment, Richard de Grijs considers the geopolitical implications of this new space race

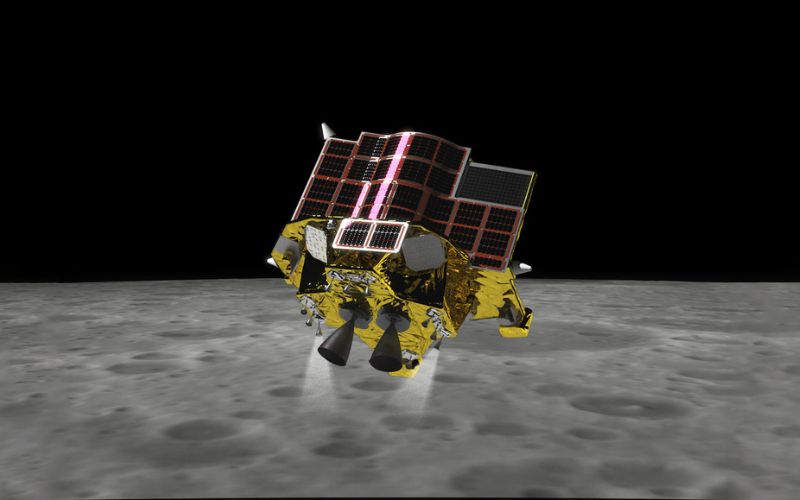

Image: Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (Jaxa)

In CRJ 17:3, we explored space as the next frontier, taking a look at the many facets of what this new growth will mean for the world. Gianluca Pescaroli (p 81) explored space technologies at length, their risks, and their vulnerabilities on earth. Johan Eriksson and Giampiero Giacomello (p 85) investigated if the liberal principles of the peaceful use of space can prevail despite the trends of militarisation, outsourcing, geopolitical jostling, and booming private investment, while Ewan Haggarty (p 91) explained the growing environmental and geopolitical complexities arising from humankind’s ever greater expansion into space.

Japan has become the fifth country to successfully land a probe on the moon. To date, the US, the Soviet Union (present-day Russian Federation), China, and India have preceded the East Asian nation, writes Richard de Grijs, Professor of Astrophysics at Macquarie University.

Launched in September 2023 by the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (Jaxa), the Japanese Smart Lander for Investigating Moon (SLIM) touched down on the moon. Trialling a novel landing technique with pinpoint accuracy, it was poised to settle on a gently sloped crater rim – a first in lunar exploration. Jaxa celebrates its mission as a technology demonstrator. The agency's main aim was to practice near-real-time visual precision landing. The newly developed landing technology allowed them to touch down anywhere they wanted, rather than only where the terrain was favourable.

Plans for a follow-up expedition, the Lunar Polar Exploration Probe (Lupex), are well advanced. That mission will be developed jointly with the Indian Space Research Organisation (Isro).

In recent years, the moon has become a key target for exploration missions. For instance, just last year, Russia attempted the landing of its Luna 25 probe, and India conducted its first successful Isro Moon shot, Chandrayaan-3. Meanwhile, the US aims to return humans to the moon through its Artemis programme while also supporting commercial companies in their quest to reestablish a viable presence there.

NASA and its international partners aim to eventually place a crewed space station in lunar orbit, the Gateway Lunar Space Station. Simultaneously, China continues its successful, carefully planned Chang'e project. The Asian powerhouse is working towards establishing its own International Lunar Research Station, a Chinese-Russian project that is promoted as “open to all interested countries and international partners.”

To date, the leading spacefaring nations have gone to great lengths to publicly assure that their intentions in space are peaceful. Yet, last year, Yury Borisov of Russia's space agency Roscosmos stated that: “it is not just about the prestige of the country and the achievement of some geopolitical goals but also about ensuring defensive capabilities and achieving technological sovereignty.”

Borisov's comments should not be read in isolation. US officials have made similar assertions. In July last year, the US assistant secretary of defence for space policy, John F Plumb, said that “space is in the DNA of the military and is absolutely essential to their way of war.”

Such official commentary is clearly anathema to the purported peaceful intentions expressed by officials elsewhere in their respective national hierarchies. In a similar vein, China has been honing its own military space strategy in order to protect its national interests, as President Xi Jinping himself encouraged.

The moon is a large target that, to date, is only accessible to a small number of actors. Yet, ever since evidence of water was found near the moon's south pole, much effort has focused on finding ways to land safely in the moon's southern hemisphere. With commercial actors and national interests thrown into the mix, we ought to consider the geopolitical implications of this new space race.

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty remains the defining legal document governing strategic conduct in space. All of the major spacefaring nations, as well as 114 other countries, have ratified it to date. However, new technological developments and the increasing presence of private space companies have prompted some to suggest that the treaty has become outdated.

Therefore, the US has independently developed a new international agreement, which it says is focused on common principles, guidelines, and best practices applicable to the safe exploration of the moon and beyond the Artemis Accords. Thus far, 33 countries have signed the agreement, but neither Russia nor China have acceded. Given the prevailing political differences, there is currently no clear way forward to bring all parties to the same table.

Although the moon remains uncrowded, sustained exploration, human occupation, and commercial exploitation will increase the probability of encounters on the lunar surface, in orbit between competing parties, or even between nations engaged in major conflict on Earth.

While the Outer Space Treaty envisions peaceful use of the space environment, the proliferation of military hardware in low Earth orbit implies that any such adverse encounter might result in devastating consequences.

At present, there are few safeguards to prevent wholesale conflict from escalating beyond the home planet. Diplomatic efforts have been largely lacklustre.

Despite urgent recommendations from across the political spectrum to practice caution and avoid escalation, the world continues on a path toward an increasingly volatile space environment.

Fortunately, in this highly complex environment, cool heads have thus far prevailed in resolving potential conflicts in space. As a case in point, the sustained multilateral collaboration on the International Space Station, despite the parties' radically opposite stances on Earth, is encouraging.

This piece was originally published in The Conversation and is being reproduced here under Creative Commons 4.0.