Stress and crisis management

Evie Whatling of Ricardo looks at how crises that occur nowadays are subject to extensive and immediate media scrutiny and how the so-called crisis management ‘golden hour’ is now more like a ‘golden ten minutes’, if that. When all is at stake, stress becomes a critical factor.

Aiming for such high standards and providing an effective response means people are vulnerable to two types of stress within crisis management - acute and chronic. Image: robuart/123rf

Consequently, when responding to a crisis, organisations and responders are being affected by increased scrutiny, particularly as such events can be witnessed by a larger audience through live news feeds, so heightening political and public attention. Failure and mistakes are becoming less acceptable, while crises are becoming more frequent and diverse. Increasingly, when the response to a crisis event is scrutinised, the focus is on what has not been done as opposed to what has been done.

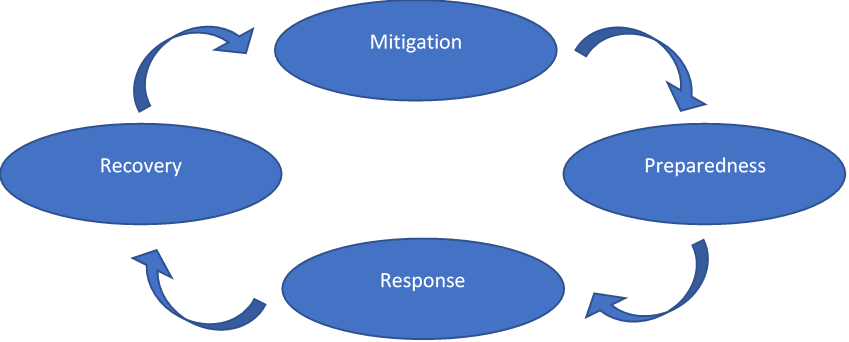

An effective crisis management system is based on four phases – preparedness, response, recovery and mitigation. All stages of this system are now critiqued upon the fallout of a crisis event to assess an organisation’s commitment to resilience.

This makes establishing such a system a stressful process because all phases will be accessible to the public eye and they need to be balanced with workplace responsibilities, professional working roles and the overall organisational strategy, mission, aims and objectives. Alongside this, the competence and confidence of staff are more important than ever.

Whether a crisis has a fast or slow onset, stress is also prevalent as agencies and organisations focus on protecting reputation, sustaining business operations, ensuring minimal consequences from a single incident and recovering successfully.

Defining stress

Aiming for these high standards and providing an effective response means people are vulnerable to two types of stress within crisis management.The first is ‘acute stress’, which is known as the fight, flight or freeze stress. Acute stress triggers action or protection during an emergency situation and is most likely to be triggered during fast-onset crises – those described as being sudden and unexpected occurrences. They spike quickly and need fast action, which will activate acute stress as people respond. This form of stress occurs swiftly, but is short-lived. Generally, this stress will only happen when an individual feels they are in a threatening or emergency situation.

The second is ‘chronic stress’, which is also called ‘workplace stress’. It tends to emerge gradually and can last for a long time. Chronic stress occurs when an individual feels overwhelmed or challenged by multiple, progressive or persistent stressors. A slow-onset crisis emerges slowly over time, has ambiguity in its development and can continue for a while – Covid-19 is such an example. Slow-onset incidents can provoke chronic stress as constant management is needed to prevent escalation and increased impacts.

Why stress is a problem for incident response

Research has identified that small, dispersed periods of acute stress can have a positive impact on a person. Acute stress increases cognitive functioning and memory and promotes motivation and alertness. However, it can be overwhelming when sustained for a long time or when a person has little experience of crisis events. This can make it damaging in providing an effective response.

An example of this can be found from the inquest into the Hillsborough disaster (1989), which reported 35 leadership failures, many of which were attributed to the police commander at the time, David Duckenfield. These failings included taking slow and inappropriate decisions as the situation developed – and worsened – around him. Duckenfield’s ability to respond was impaired owing to his lack of experience at football events which triggered a freeze response once his acute stress was activated. According to witness accounts, this meant that he became withdrawn, detached and disengaged from surrounding activities which had an impact on the overall outcome to the event (Hillsborough Independent Report, 2012).

Particular traumatic events can also cause responders to develop acute stress disorder, which is the difficulty to process an event and its effects. Acute stress disorder has very similar effects to those of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) – and PTSD can emerge from acute stress disorder.

Chronic stress can emerge and develop from slow-onset incidents. However, it can also emerge from sustained pressure and scrutiny following a response which can continue for weeks, years and even decades. This can affect the health and wellbeing of individuals involved and disrupt their ability to recover fully.

Both types of stress impact the response to and recovery from crises. Stress can become overwhelming during a crisis event. Those affected may struggle to make effective decisions and communicate the right information to the right people and might make assumptions and link information that will create an inaccurate understanding of what is happening. These can then result in challenges to leadership and team co-operation.

Problem for our personal health and wellbeing

As mental health gains more traction and attention, responding to traumatic events is being recognised as a trigger for long-lasting mental health conditions.

Those who are responsible for responding to crisis events are expected to do so effectively and efficiently. However, the mental health struggles and stress management requirements that are aligned to these types of events are often overlooked.

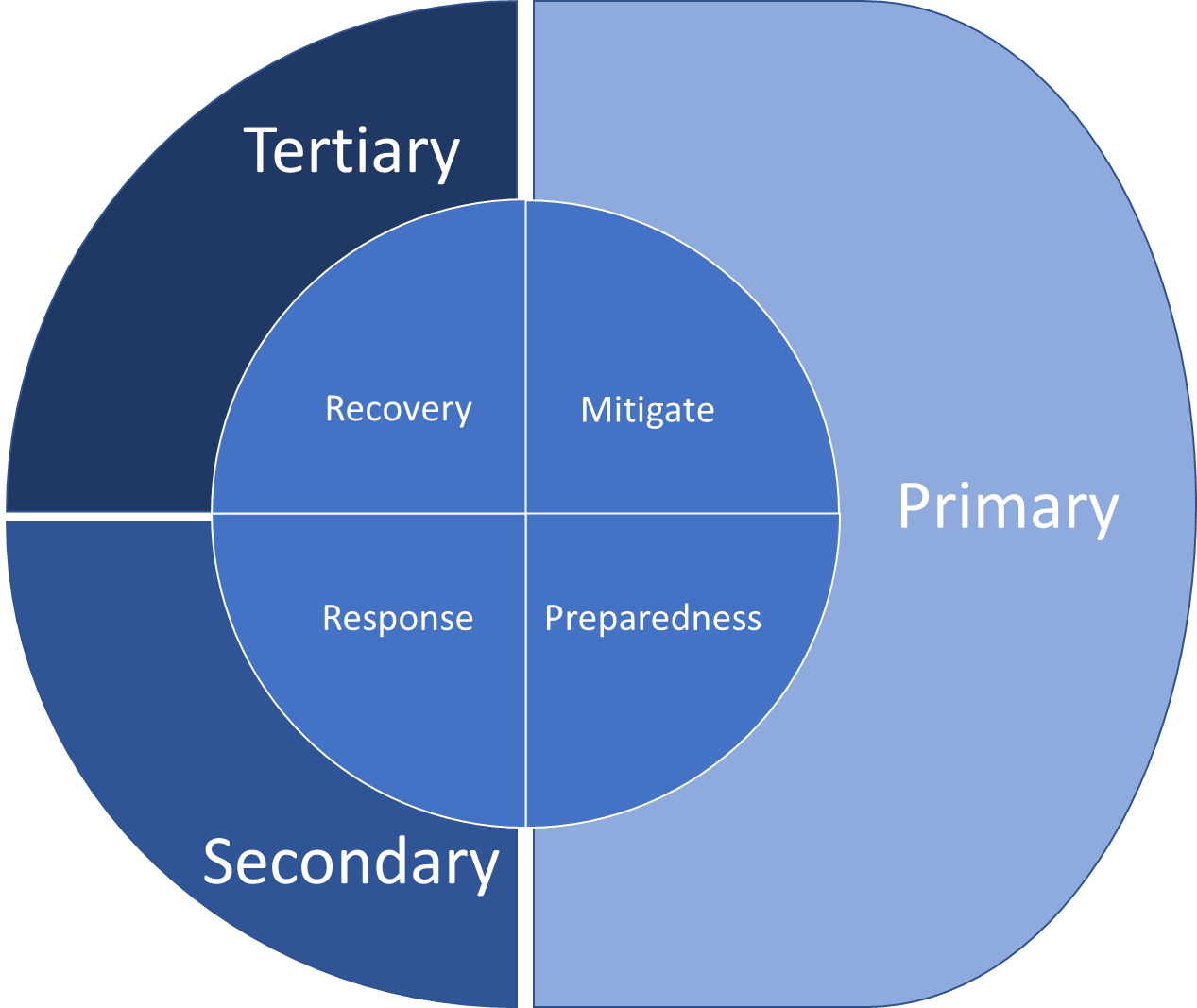

No longer can the emergency management cycle purely focus on processes and procedures – each stage should be expanded to include the ‘people’ element. In this case, it means including appropriate support and awareness of stress management and mental health needs at every stage. This is most effective when this extends over various levels – from the organisational culture, plans and structure, through to the response teams and leaders and to the individual. This can be incorporated in the emergency management cycle through primary, secondary and tertiary intervention measures.

Primary interventions focus on reducing, removing or minimising the exposure to stressors and is best considered during the mitigation and preparedness stages of crisis management. Secondary interventions are mechanisms to support the safe response and management of stress once it emerges during the response to a crisis. Tertiary interventions are mechanisms to support the full recovery of personnel which can continue for days, months, or years following an event; this can be particularly challenging when the event is investigated for a long period of time.

Making sure an appropriate and diverse range of tools are available is important to the care and support of crisis management teams and the maintenance of personal and organisational resilience which will sustain the performance of the crisis management framework.

Evie Whatling, 08/07/2020