Conflict and Covid-19

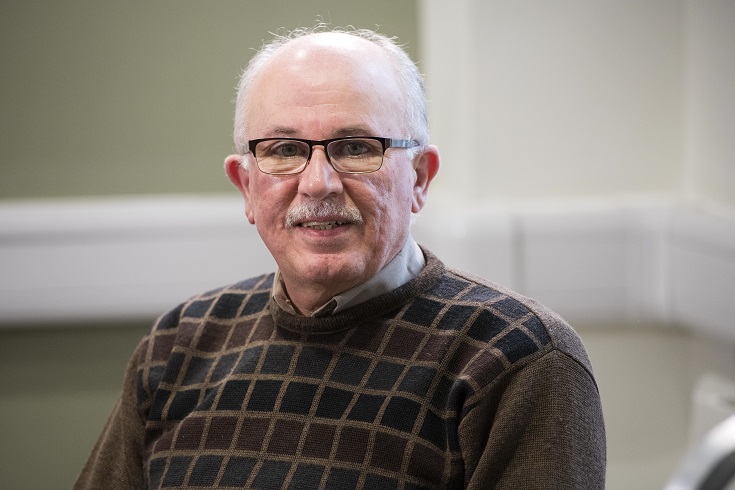

Dr Ayman Jundi, Senior Lecturer at the University of Central Lancashire (UCLan) and Chairman of the Board of Trustees at Syria Relief, says that the challenge of dealing with a pandemic is compounded by degraded healthcare infrastructures in complex and volatile conflict zones.

The unavailability of any testing kits in Syria meant that authorities had little or no idea about the number of cases in the community and no viable planning was possible to try to limit the spread of the illness. Image: Submitted to the United Nations Covid-19 response - UN's Open Brief /Unsplash

Covid-19 is, undoubtedly, the most extraordinary healthcare challenge of our generation. Public health systems in some of the most civilised nations have had their weaknesses and deficiencies exposed, and the most robust, well-equipped and well-funded healthcare systems have been seriously stretched and in some cases, overwhelmed.

The images of very sick patients lying on trolleys in the corridors of hospitals in some of the most sophisticated and advanced facilities in the world will remain vivid in our memories for years to come. Now imagine having to deal with the pandemic in an area where violence against civilians and heathcare infrastructure has been rampant for nearly a decade.

The conflict that continues to ravage Syria entered its tenth year in March, just as the Covid-19 pandemic was starting to take hold. A particularly disturbing hallmark of the ongoing crisis in Syria has been the deliberate and concerted assault on healthcare facilities, in brazen disregard of International Humanitarian Law. These attacks continue with complete impunity, despite the persistent protestation of all humanitarian agencies that are active on the ground in Syria and despite the active and focused lobbying that they collectively carry out at every relevant forum, both regionally and internationally.

These persistent attacks on healthcare facilities have resulted in a poorly structured, thinly staffed and meagrely equipped system that would prove to be unfit to face up to a serious pandemic effectively.

In any healthcare system, the first step in attempting to deal with a pandemic must involve reliable community testing to get the necessary information about the spread of the disease in a community. The unavailability of any testing kits in Syria meant that authorities had little or no idea about the number of cases in the community and no viable planning was possible to try to limit the spread of the illness.

It took many weeks of uncertainty before any semblance of reliable testing could be introduced at a significant scale. In areas outside the Regime control, where the healthcare infrastructure is particularly dysfunctional, it took several more weeks before humanitarian organisations were able to procure testing kits and set up appropriate lab facilities in the region or, alternatively, provide secure access routes to ensure that tests performed would safely reach established lab facilities in Turkey, Syria’s influential northern neighbour.

Comprehensive, reliable testing is still patchy throughout Syria, particularly in areas of Northern Syria outside the Regime control.

In the UK and other developed countries, lockdown and social distancing have been the backbone of the strategies that helped to control the spread of the disease, especially in the current absence of any reliable treatment or effective vaccine. However, maintaining any meaningful level of social distancing or lockdown in refugee camps is practically impossible to implement. Poor sanitation and inadequate hygiene facilities bring with them the added worry of waterborne and foodborne disease.

Humanitarian organisations that have tangible presence on the ground, such as Syria Relief (www.syriarelief.org.uk), worked extremely hard to augment their Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WaSH) programmes, and rapidly developed effective awareness videos, lectures and seminars, which were introduced widely to try and alert communities to the dangers of the disease, and to provide advice on the importance of hygiene and social distancing. These awareness and training sessions were very well received, and it is hoped that they had some significant impact in reducing the spread of the disease into the organisation’s areas of operation.

In addition, Syria Relief, along with other humanitarian agencies, launched numerous campaigns and appeals to raise money to buy face masks and sanitation equipment that could be distributed in refugee camps and throughout the internally displaced communities.

Responsible and safety-conscious humanitarian organisations immediately recognised that much of what they did involved close contact between aid recipients and beneficiaries and between different recipients. Prevailing practices at the time, for example, involved recipients attending distribution centres to collect food baskets, hygiene kits and other items, often in large numbers.

Clearly, with the prevalence of Covid-19, the infection risk as a result of such practices became totally unacceptable. Therefore, humanitarian organisations rapidly modified their policies and procedures to ensure that they strictly comply with the highest standards of personal hygiene, hand sanitation, and social distancing.

At Syria Relief, extensive staff training for all staff on the ground in all matters relating to hand hygiene, social distancing and other relevant procedures was undertaken. A strict delivery programme was implemented, which meant that staff would deliver aid kits and items to the recipients’ homes and residences while maintaining the strict rules of social distancing at all times.

Dr Ayman Jundi is a Consultant in Emergency Medicine at Lancashire Teaching Hospitals, and a Clinical Senior Lecturer in Disaster Medicine at the University of Central Lancashire. He trained in Damascus and worked at the American University in Beirut at the height of the civil war in Lebanon. He is a founding trustee and Chairman of the Board of Trustees at Syria Relief, a charity that supports and cares for displaced people. Photo: UCLan

The procedures that were visible and tangible in every aspect were very welcome and widely appreciated by recipients, who were relieved to see that aid organisations had beneficiaries’ safety and wellbeing at the top of their priorities. In addition, and as an added bonus, the clearly visible nature of the precautionary measures adopted by aid organisations has helped to raise more awareness in communities about the dangers of disease transmission and the importance of adopting all necessary precautions to limit it.

The immediate and time-critical actions of Syria Relief and other humanitarian organisations did not happen by accident. They were the result of proactive, considered and deeply thought-out processes that had been instilled into the minds of senior staff, planners and advisors through their training and experience. And although none of them had ever been through anything like the Covid-19 pandemic, their actions were prompted by visionary, innovative and creative thinking engendered by focused and targeted training and then nourished and developed over years of practice.

The MSc Disaster Medicine course offered by UCLan delivers the kind of innovative training that will prove its worth in such circumstances. Launching in September 2020, the course will offer an exciting opportunity for healthcare professionals who wish to be involved in the delivery of medical relief in disasters, locally, nationally or internationally. Majoring on the crucial links with humanitarian medicine, the course will provide important insight into the significance of training and capacity building on the ground, an investment that will long-outlast the presence of external relief teams on the ground, to leave a true legacy of lasting knowledge, expertise and preparedness.

Find out more about studying MSc Disaster Medicine at UCLan.

UCLan’s School of Medicine offers a range of postgraduate and professional programmes that can be studied full-time or part-time, many with online delivery and the option to start in September or January. For the full portfolio, visit the website here.

Ayman Jundi, 19/06/2020