WannaCry ransomware and the Hurricane Katrina Syndrome

Dr David Rubens of Deltar-TS looks at the recent WannaCry ransomware attack, likening its effects on the UK’s National Health Service to what he terms ‘Hurricane Katrina Syndrome’

“Most man-made disasters and violent conflicts are preceded by incubation periods during which policy makers misinterpret, are ignorant of, or flat-out ignore repeated indications of impending danger” (Boin & t’Hart, 2003)

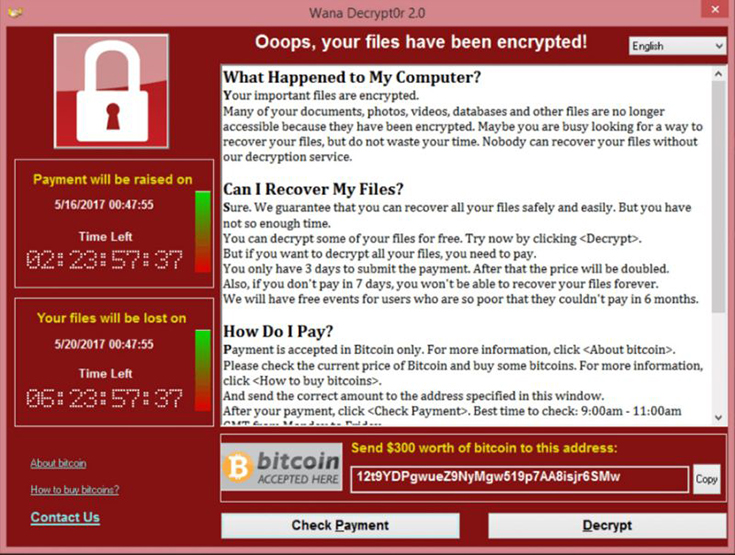

Along with major organisations in over 100 countries worldwide, the UK National Health Service (NHS) recently suffered a series of ransomware cyberattacks that either closed down its IT systems, with a threat of total destruction of the systems unless a ransom was paid, or caused other parts of the system to close down their systems to prevent further spread and infection.

Once again, this has been described as the result of an attack from outside – though this time at least, for criminal purposes rather than terrorist objectives – but it became clear almost immediately that this attack falls into a classic format of a known vulnerability being ignored by people in charge, even though they were fully aware of the potential catastrophic consequences of inaction, and had been given multiple small-scale warning of the effects of what would be a full-on attack.

Hurricane Katrina Syndrome

“Despite the understanding of the Gulf Coast’s particular vulnerability to hurricane devastation, officials braced for Katrina with full awareness of critical deficiencies in their plans and gaping holes in their resources” (US Congress, 2006)

What might be called the ‘Hurricane Katrina Syndrome’ is not confined to the NHS, or any of the other countries that were involved, but it is something from which all risk managers can (and should) learn, whatever the nature of the organisation they are involved in.

This latest attack cannot be claimed to be unexpected. In fact, given the changing nature of cyberattacks, it is clear that the combination of a high level of organisational criticality – combined with a diffused and de-centralised systems network that allowed both multiple points of entry to be used to access every other area of the system, tied in with the chronic underfunding of appropriate security measures, meant that the IT systems in the NHS were little different to the Bank of England leaving the doors to its main gold vaults open to any passers by.

The study of the failure of what are supposedly High Reliability Organisations is a central part of the Deltar Level 4 Advanced Risk and Crisis Management programmes that we now run for senior risk managers all over the world. I think it is worth repeating some of those lessons here, highlighted in the official reports into major global events that were themselves the result of Hurricane Katrina Syndrome. It is not difficult to see how the insertion of the words ‘NHS’ into each of these reports would mean that they would be exactly describing the chain of organisational, managerial and policy failures that were the direct cause of the vulnerabilities that led to the attacks being able to be made both so easily and so successfully.

From the Space Shuttle Challenger Report

There was: “Pressure throughout the agency that directly contributed to unsafe launch operations. The committee feels that the underlying problem that lead to the Challenger accident was not poor communications or inadequate procedures …. The fundamental problem was poor technical decision-making over a period of several years by top NASA and contractor personnel…. Information on the flaws in the joint design…. was widely available, and had been presented to all levels of shuttle management… there was no sense of urgency on their part to correct the design flaws in the SRB.”

The board: “Considered it unlikely that the accident was a random event; rather, it was related in some degree to NASA’s budget, history and programme culture, as well as to the politics, compromises and changing priorities of the democratic process,” the report said, adding: “We are convinced that the management practices overseeing the Space Shuttle Programme were as much a cause of the accident as the foam that struck the left wing.”

From the Deepwater Horizon Report

These failures (to contain, control mitigate, plan and clean up) appear to be deeply rooted in a multi-decade history of organisational malfunction and shortsightedness. There were multiple opportunities to properly assess the likelihood and consequences of organisational decisions, ie risk assessment and management… As a result of a cascade of deeply flawed failure and signal analysis, decision-making, communication and organizational-managerial processes, safety was compromised to the point that the blowout occurred with catastrophic effect.”

It becomes clear from reading these reports that the events that they describe are not random, unexpected or without cause. They are, in fact, the inevitable result of people in management positions consciously deciding to ignore problems which they are aware of, but which they have no intention of dealing with. The question that should be asked is not ‘Why did this happen?’ but ‘Why did we not do something about it?’

Pathway to disaster

The organisational weaknesses that are the precursor to almost all disasters of this nature were identified by Charles Perrow in one of the most influential books on understanding, and managing disasters. In book Normal Accidents: Living with High-Risk Technologies, Perrow identified the ‘Pathway to disaster’ that can act as a quick test for identifying the inbuilt vulnerabilities that are almost certain to lead to a high-impact (and possibly catastrophic) event.

The crisis is the result of weaknesses within our own systems, not the result of an outside event. There is a series of low-level ‘normal accidents’ that highlight those weaknesses – but these are ignored. And when the crisis is triggered, it is not recognised as a crisis because people think that it is the same as the previous low-level ‘accidents’

When you start to react to the disaster, there are three shortages:

-

Equipment

-

Manpower

-

Management skills

When you do react to the crisis, it does not respond as predicted (Law of Unintended Consequences)

Lessons are not learnt after the crisis is finished; once a disaster is over, it can be clearly seen that it was an inevitable consequence of systemic weaknesses that were known, and ignored.

What happens next?

The question now is not: “How do we fix the NHS”, but: “How can we keep our critical national infrastructure safe form similar attacks – especially at a time when there is chronic underfunding, a lack of rational management structures that means that no-one is actually responsible for ensuring the safety and security of the systems, and when the speed of the evolution of cyber-threats is such that solutions that are effective today will undoubtedly be outmoded in three months time?”

What if the next attack affects the global banking system, nuclear power stations, national transport, air traffic control, or global communications?

It would be nice to think that somebody, somewhere, is actually thinking about these questions in a serious manner.

An expanded version of this article will be published in the August/September issue of the CRJ.

References

-

Boin, A, & Hart, P T (2003); Public leadership in times of crisis: mission impossible? Public Administration Review, 63(5), 544-553;

-

United States Congress (2006): Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina, & Davis, T (2006): A failure of initiative: Final report of the select bipartisan committee to investigate the preparation for and response to Hurricane Katrina. US Government Printing Office. Available here;

-

Investigation of the Challenger Accident

-

Columbia Accident Investigation Board

-

Deepwater Horizon Report

-

Perrow, Charles (1984): Normal accidents: Living with high-risk technologies. Princeton University Press

Further Reading

Two books that set the foundation for the study and modelling of technical failures are

-

Toft, B, and Reynolds, S (1994): Learning from Disasters, a Management Approach; and

-

Turner, BA and Pidgeon, N (1997): Man-Made Disasters, Butterworth-Heinemann

-

If you want to read one book on the subject, the author recommends The Next Catastrophe: Reducing Our Vulnerabilities to Natural, Industrial, and Terrorist Disasters, also by Charles Perrow, published in 2013, available here

Deltar Training Resources

For information on the Deltar ‘Level 4 Management Award in Advanced Corporate Risk and Crisis Management, please visit:

For access to Deltar's library of free resources, including reports, academic papers, magazine articles, interviews, links to professional and academic databases, and a whole lot more, please visit

Dr David Rubens, 16/05/2017